Kim Gentes |

Kim Gentes |  1 Comment |

1 Comment | In the past, I would post only book reviews pertinent to worship, music in the local church, or general Christian leadership and discipleship. Recently, I've been studying many more general topics as well, such as history, economics and scientific thought, some of which end up as reviews here as well.

Saturday, April 20, 2013 at 12:33AM

Saturday, April 20, 2013 at 12:33AM  Church government is a topic that has as many opinions as there are churches. In fact, though the Bible talks little about church government directly, it is a main point of distinction among many Christian groups. This is both sad and telling of our fractured world and the bride of Christ. Because of this lack of cohesion, teaching and discussion among Christians on this topic, there are few writings on the subject that don't devolve into particularism.

Church government is a topic that has as many opinions as there are churches. In fact, though the Bible talks little about church government directly, it is a main point of distinction among many Christian groups. This is both sad and telling of our fractured world and the bride of Christ. Because of this lack of cohesion, teaching and discussion among Christians on this topic, there are few writings on the subject that don't devolve into particularism.

One book I have recently read on this subject is Danny Silk's "Culture of Honor: Sustaining A Supernatural Environment". Silk is a senior staff member at Bethel Church in Redding California, most known for its popular leader, Bill Johnson. "Culture of Honor" is a different approach to church government than you might expect. It's main distinctive is embedded in the title of book- that the honor of people is the only way to true leadership of those same people. This is stated upfront in a succinct definition:

The Principle of Honor states that: accurately acknowledging who people are will position us to give them what they deserve and to receive the gift of who they are in our lives.1

Silk provides both strong points and excellent personal/church examples of those points throughout the book. The examples shine of the vibrancy of mercy, wisdom and faith that takes both God and people seriously. It is clear that Silk (and the book therein attributes this clearly also to Bethel) is looking to undermine the assumption of a business world influenced hierarchical church government and supplant on it primarily the pastoral care of mercy and wisdom within the context of a relational, not structure, based leadership. This is somewhat ironic because one of the main refutations that the book makes is actually a claim against the role of pastoral office as a primary overseer of the local church. But I will return to that later.

What I love about this book is it's common sense, and biblically based, understanding of its main thesis- that we are to honor people with the assumption of good in our hearts. Judgment is not an option, and even as leaders, we do not assume acts of "church discipline" are the first solutions to people's failures. In fact, Silk is almost masterful in his application of the Socratic method (guiding people through asking questions as a way of self-discovery) of pastoral counseling. He knows, like great leaders in history have always known, that people change only through internal acknowledgement and willingness to do so. This can often only come when those people are empowered through revelation of their own situation, failures, misunderstandings and sin. None of this can be imputed (and make a heart change) by typical "instructive" methods. Silk rightly leans on this key point:

Asking the right questions in the right way is one of the keys to creating a safe place.2

The author culminates a series of excellent examples into several poignant truths, debunking the need to chastise people into submission, and taking the message of Jesus mercy as the prevailing guideline for our actions, rather than the judgment and criticism so prevalent in many church governmental structures. He confronts this issue of judgment and its fallout head-on:

What offense does to you is it justifies you withholding your love. I get to withhold my love from you when you have broken the rules, because people who fail are unworthy of love, and they deserve to be punished. In fact, what punishment looks like most often is withholding love. And when I withhold love, anxiety fills the void, and a spirit of fear directs my behavior toward the offender.3

This brilliant statement is a cogent explanation of so many of Jesus teachings on leadership and sin, especially the specific lessons he was pointing to in his parables of the good Samaritan and the prodigal son. Silk, and Bethel, seem to have found an articulation for how to apply these deep truths that rises above the need to control people, based on their fear of "getting messy" with difficult situations and people. The book pivots on the idea that "we are un-punishable"4, which is related not only as a core value but a culture changing reality for the church and the world- and who can argue with him! Silk has found in church government a place in dire need of the cross and Christ's work on it- the mercy of God, removing judgment from our realm to God's.

For these points, "Culture of Honor" is one of the best books you can read on church leadership and how to lead in relational grace rather than shaming or controlling people into "Christian behaviors". Interestingly enough, after recently finished reading Brené Brown's "Daring Greatly", I found that "Culture of Honor" is (at its core) a biblical exposition of the truths Brown discovers (through her research), that shame ultimately always fails as an effective motivator and leadership tool. An odd juxtaposition, to be sure, yet these books are linked in their foundational message of leaving shame-based methods and moving to forms of trust (in Brown's book vulnerability; in this book faith) that provide relational, not positional, power to influencing others.

Silk is expressive in his passion for his viewpoint and one can't argue with his experience for which he claims to be witness to the power of his model being operable- presumably, the church community he is a part of thrives in the leadership architecture of he describes in the book. As I said, I enjoyed the book and found its primary points- honoring people, valuing their worth, Socratic-method counseling/pastoral care, creating safety in community and confrontation, the value of Christ's work making us un-punishable, avoidance of shame-based manipulation, faith/risk/vulnerability, reliance on the Holy Spirit, viewing the "on earth as it is in heaven" of Matt 6 as the primary perspective of God's kingdom intersecting and invading our real world, the inclusion of apostolic and prophetic ministries as essential components to local church leadership- to be excellent examples of the mercy-centered orthopraxy from which Jesus himself modeled ministry.

But to give this review its full treatment I must state where I felt the book falls short of what appears to be one of its main goals- to establish a new "order" of hierarchical rank in local church government. Specifically, Silk uses 1 Corinthians 12:28, which says "And God has appointed in the church, first apostles, second prophets, third teachers, then miracles, then gifts of healings, helps, administrations, various kinds of tongues."5 to attempt to justify this assumption about a hierarchical order of church government:

Paul clearly lays out an order of priority in this passage, and this order is related to the realms of the supernatural that correspond to each particular office.6

From this assumption, the author builds a lengthy argument and reasoning around establishing apostles as the current positions which should play the foundational role in church government. The problem is, he does not substantiate it well from scripture. One has to make the interpretive jump with Silk that "first...second...third" was implicit to authority and NOT to order of operation or a timeline. Further, the context of this entire section of Corinthians is actually the inverse point that the Silk is trying to draw from this single passage in a few ways.

View a detailed review of points that I felt were poorly made in this book.

This is disheartening, because (as I mentioned at the outset) this book has some excellent things to say. I love the main premise (and title) of the book, I agree with much of the foundational and grace-centered basis of the Bethel approach to leadership and conflict resolution, and I even like the important reconsideration of the roles of apostle and prophet into the local church government. However, the support and exploration of the church governmental theory is so poorly done as to undermine the value of the hypothesis. I am not even saying the hypothesis couldn't be true- I just don't think this book does a good job of doing that. Also, the tone of the book, at times, does not help endear the reader to give more benefit of the doubt to the author. At times, it sounds self-assured and perhaps even condescending to those who might not agree (a la "you might think you know, but listen, we've got this figured out"). I just think a bit more language of "consider this" throughout the book would have taken it from being a book that sounds sure of itself, to being one that church leaders might want to chew on and consider its points more seriously.

In the end, despite my long and detailed comments of frustration (mentioned above), I strongly recommend people read this book. Especially to any church leaders who are looking for insightful perspectives on church government. Struggle with this book, as I did. Read the stories, be inspired by them. And try to untangle the disconnected logic from the main ideas. As one church leader said "eat the meat, spit out the bones". I initially read this book as an assignment, and when I was finished I thought "I could definitely serve at a church with that model". I'd use this book to explain the model- as it does that well- I just wouldn't try to use this book to defend it.

Amazon Link: http://amzn.to/11qULKf

Review by Kim Gentes

1. Silk, Danny (2009-12-28). Culture of Honor: Sustaining a Supernatural Enviornment[sic] (Kindle Locations 179-180). Destiny Image. Kindle Edition.

2. Ibid., (Kindle Locations 318-319)

3. Ibid., (Kindle Locations 1076-1079)

4. Ibid., (Kindle Location 1181)

5. Ibid., (Kindle Location 566-568)

6. Ibid., (Kindle Location 569-570)

7. Ibid., (Kindle Location 720-721)

8. The prophetic model of Old Testament scripture, that Jesus did come to fulfill, is one of a Godly criticism to the people of Israel. Unlike our idea of explaining the future, most of what is labeled prophetic in the old and New Testament is the balancing critique of Gods voice. Often confronting, correcting compelling and reframing people's expectations and worlds against the call of God. Again, prophetic certainly does have a revelatory nature of all its operation but its clear that scripture most often has it as a balancing voice of insight meant to keep the Israel/the church from become self focused.

9. Silk, Danny (2009-12-28). Culture of Honor: Sustaining a Supernatural Enviornment[sic] (Kindle Location 746-747). Destiny Image. Kindle Edition.

10. Ibid., (Kindle Location 1326-1328)

Kim Gentes |

Kim Gentes |  1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:29PM

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:29PM  Elias Chacour is a Melkite Palestinian priest living in Galilee. He is a central figure in reconciliations efforts to draw an end to the persecution and expulsion of Arabs from the Jewish country of Israel. The territory occupied by Israel following the establishment of the state (after World War II), created a polarized ethnic feud, perpetrated by Zionist Jews (claims Chacour) that have resulted in the persecution of Palestinians. In his book “We Belong to the Land”, Chacour outlines his struggles as a priest and local leader in a the community of Ibillin. In that small community, Chacour fights to build unity amongst different people groups, religions and ages. His efforts include building a unified inter-faith group, constructing and managing a secondary school and high school, and eventually a college. The struggles Chacour outlines, explore the racist and discriminatory efforts of Jewish establishment officials to minimize the rights and opportunities of Palestenians in an effort to force them to leave the country (allowing the Jews to have a completely Zionized state).

Elias Chacour is a Melkite Palestinian priest living in Galilee. He is a central figure in reconciliations efforts to draw an end to the persecution and expulsion of Arabs from the Jewish country of Israel. The territory occupied by Israel following the establishment of the state (after World War II), created a polarized ethnic feud, perpetrated by Zionist Jews (claims Chacour) that have resulted in the persecution of Palestinians. In his book “We Belong to the Land”, Chacour outlines his struggles as a priest and local leader in a the community of Ibillin. In that small community, Chacour fights to build unity amongst different people groups, religions and ages. His efforts include building a unified inter-faith group, constructing and managing a secondary school and high school, and eventually a college. The struggles Chacour outlines, explore the racist and discriminatory efforts of Jewish establishment officials to minimize the rights and opportunities of Palestenians in an effort to force them to leave the country (allowing the Jews to have a completely Zionized state).

Unlike his other book, Blood Brothers, Chacour focuses this book on details of injustice, his programs and building efforts, his organization and leadership across Galilee, Israel and around the world. Much of the book includes his philosophical and rhetorical foundation for his opposition to Jewish radicalism within the occupied territories where Palestinians once thrived. Chacour is a brilliantly practical man, with wit wisdom and far reaching appeal. He intuits things that others only come to understand through years of deep thinking and research. For example, he speaks eloquently about the value of human beings:

"The true icon is your neighbor", I explained to my companions on Mount Tabor, "the human being who has been created with the image and with the likeness of God..."[1]

We Belong to the Land especially follows the details of corruption not only with the the Zionist corners of the Israeli government, but scandalous and complicit efforts of Chacour’s own overseer, the local Bishop of his church’s diocese in which he is serving. In fact, corruption of values across the church and even “western” society is brought largely into focus by Chacour’s damning indictments of the “Christian” supported US government’s efforts to support and sustain Israel’s policies.

Much of what Chacour elucidates he does so as we follow the story of his building of his local school in the community of Ibillin. The seemingly simple matter of securing a building permit becomes the plot device which allows us to explore the broader injustices to both Ibillin and the Palestinian people. But Chacour is careful not to become the very thing he despises, which is common a trend. Instead of hating the Jewish people who have repressed the Palestinians in the country, he constantly calls for a fellowship of love in which both people’s can live in harmony within the land. His most articulate arguments become prayers of commonality that we can all join in. He says,

Human worth, human qualities, are much more important than Jewish, Palestinian, or American nationalism, peoplehood, or land. Sometimes it seems to me that Zionism pushes the Jews to Zionize themselves rather than humanize themselves.[2]

His thesis in the book centers around his belief that the thousands of years of living in the land have united the Palestinians with the essence of what it is to be an agrarian people.

Mobile Western people have difficulty comprehending the significance of the land for Palestinians. We belong to the land. We identify with the land, which has been treasured, cultivated, and nurtured by countless generations of ancestors.[3]

The examples and clarity of Chacour’s convictions become crystal clear. He is intent on peaceful freedom for Palestinians within the national borders of Israel. But for all his brilliant practicality, Chacour takes his altruism and misapplies it at least once, when he says,

God does not kill, my friends. God does not kill the Ba’al priests on Mount Carmel, or the inhabitants of the ancient city of Jericho. God does not kill in Nazi concentration camps, or in Palestinian refuge camps, or on any field of battle.[4]

It is obvious to many that Elias Chacour reflects the best of a heart of justice found in our world today. Yet, we cannot, even in our desire for justice, pretend to know more than God. God, in fact, is more just than us, and more loving than us. But He did kill, not just people in the Old Testament (uncountable peoples of all the inhabited the land of Canaan that were wiped out as Israel settled and conquered the region, including both of the instances of Ba’al preists and Jericho inhabitants that Chacour blatantly denies God is responsible for, though the text clearly indicates He is), but people in the New (Ananias and Sapphira, plus the multitudes of opposition to Jesus righteous judgments in John’s Revelation). While we have a hard time reconciling those actions to our comprehension of a loving God, we cannot dismiss God’s actions of these final earthly judgements of death as though they didn’t happen or he didn’t mean it. He did, and He is still God. Misstating these facts to shape God into your vision of justice does not do God, himself, any justice.

The other (more dangerous) issue to me on the above quote is that Chacour combines things that God clearly does instigate (Jericho and Mt. Carmel) with things that man (or perhaps Satan himself) have deeply inspired and carried out (Nazi Germany, Palestinian refuge camps). One cannot attribute all evil actions to God, unless one decides to make man faultless of his own predilections, choices and sinfilled actions. Of course, there is the grand question "why do bad things happen to good people" and why is there suffering and hurt. The short answer is - sin. But there are rife volumes and lives spent on the topic, so I won't pretend to sort that all out here. But munging God's clear actions and man's sinful ones in a single list of activity (as though they belong together) is a terribly grievous error, for which I cannot let go without mention.

My confidence in his writing flags when I see that he never actually deals head on with the specific claims of moderate Zionist Jews who believe they are following an edict from God to reclaim the land granted to Abraham (and therefor, Israel) by Yahweh. I am convinced that he is a man of integrity, and certainly not afraid of confrontation and working against the norm, so it surprises me that he never broaches the subject from the Jewish point of view, even if to discredit the weak points of their argument. Second, he takes the broad tact that all Christians (and especially all American Christians) are somehow in rabid support of Jewish Zionism. Again, he washes his hands of details and accuses the US of global blood guilt without taking on specifics and details from which a more reasonable (balanced) response could be given to his condemnations. It feels a little like he deals so beautifully with the story of the Palestinians that he doesn’t want to address the 800lb gorilla issue in the room- the contrary story which lives along side him every day- the Jewish Israeli claim to the land of Canaan, promised to them through the Old Testament scriptures.

I feel quite guilty having brought up what I think are short comings of his fine book, since one feels ultimately humbled and speechless in light of such a great witness of Christ’s love and reconciliation. I am very glad to be wrong on all my points, and would feel better about it. For me, the things I have said negatively don’t deter from his great accomplishments or his stature as a preeminent leader of peace in our generation. It is hard not to love the heart, desires and unbelievable work ethic of Elias Chacour. The accomplishments he has made in the midst of being a nearly singular voice within a tragic situation is remarkable. He has much to teach the world about the true nature of reconciliation and its practical outworking. I would love to meet him.

Amazon Book Link: http://amzn.to/w5PTZ2

Review by Kim Gentes

[1]Chacour, Elias & Jensen, Mary “We Belong to the Land”. (Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press 2001), Pg. 46

[2]Ibid., Pg. 69

[3]Ibid., Pg. 80

[4]Ibid., Pg. 163

arab,

arab,  chacour,

chacour,  christian,

christian,  conflict,

conflict,  elias,

elias,  israel,

israel,  palestine,

palestine,  palestinian,

palestinian,  priest,

priest,  reconciliation in

reconciliation in  Book Review,

Book Review,  Church,

Church,  Community,

Community,  Grief,

Grief,  Justice,

Justice,  Leadership,

Leadership,  Loss,

Loss,  Persecution,

Persecution,  Reconciliation

Reconciliation  Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:15PM

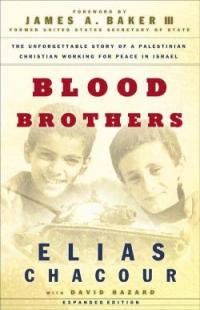

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:15PM  "Blood Brothers" is the first book from Palestinian Israeli Elias Chacour. Elias is a Christian priest and community leader in Galilee, Israel. He lives and serves his community of Palestinian Christians in a village of Muslim, Druze and Christian villagers. This book is the personal story of his youth, the expulsion of him and his family from his home village of Biram, his training as a Melkite priest, and his eventual work in the ministry of bringing hope to a broken and terrified group of alienated Arabs in Jewish Israel. Unlike his other book We Belong to the Land, Chacour focuses more poignantly in Blood Brothers on his personal and family life. Most profoundly, he explores the character of his father who serves as an arch-type for both God and the image of what good men can be. Elias Chacour treasures and follows this image into a lifetime of seeking reconciliation, hope and love for the Palestinian people of the village of Ibillin.

"Blood Brothers" is the first book from Palestinian Israeli Elias Chacour. Elias is a Christian priest and community leader in Galilee, Israel. He lives and serves his community of Palestinian Christians in a village of Muslim, Druze and Christian villagers. This book is the personal story of his youth, the expulsion of him and his family from his home village of Biram, his training as a Melkite priest, and his eventual work in the ministry of bringing hope to a broken and terrified group of alienated Arabs in Jewish Israel. Unlike his other book We Belong to the Land, Chacour focuses more poignantly in Blood Brothers on his personal and family life. Most profoundly, he explores the character of his father who serves as an arch-type for both God and the image of what good men can be. Elias Chacour treasures and follows this image into a lifetime of seeking reconciliation, hope and love for the Palestinian people of the village of Ibillin.

One such powerful example is his father’s statement about Jews and Palestinians, which he declared before the full extent of persecution would begin for the Palestinians:

“But How do we know the soldiers won’t harm us?” Rudah pressed him.

Father smiled, and all the tension seemed to relax. “Because,” he said, “the Jews and Palestinians are brothers-blood brothers. We share the same father, Abraham, and the same God. We must never forget that. Now we get rid of the gun.”[1]

This image turns out to be misinformed, though hopeful premonition to the tragedy that would ensure. After taking over the land of Palestine, the Jews of Israel began to programmatically terrorise the people of the rural villages such as Biram. Demolishing their homes and farms and confiscating the land became the program of the Zionist Jews. Even thought Chacour’s father has his land taken from him and his home destroyed, his connection to the land and its plants shows a level of care foreign to us.

I could scarcely believe it! His life's work had just been torn from his hands. His land and trees-the only earthly possessions he had to pass on to his children-were sold to a stranger. And still Father would not curse or allow himself to be angry. I puzzled at his words to us. Inner peace. Maybe Father could find this strength in such circumstances. I doubted that I could....

Father's other response to the sale of his land was more of a wonder to me. In a few weeks we heard that the new owner of our property wanted to hire several men to come each day and dress the fig trees, tending them right through till harvest. Immediately, Father went to apply for the job, taking my three oldest brothers with him. They were hired and granted special work passes, the only way they could enter our own property.[2]

Elias portrays his father with such magnanimous character that he seems barely real to our western sensibilities and callousness. The story of Blood Brothers is much deeper than just Elias Chacour’s life, it is a story of the non-violent Palestinians who are persecuted as evil by Israeli government programs meant to lodge them from hope and from land within the Galilee communities. Chacour is not just a concerned priest, he is a thoughtful change agent and leader. Speaking about the inversion of the Jews from persecuted to the persecutors he says :

Now I determined to find out how a peaceful movement that had begun with a seemingly good purpose-to end the persecution of the Jewish people-had become such a destructive, oppressive force. Along with that determination, I was driven by a respect for history that Father had planted in me. Did the seeds of our future hope lie buried in our past, as he had so often said?[3]

Elias is brilliant to turn to the teaching of his father to recall the thought that history can teach us and, perhaps if heard, can lead us back together. Blood Brothers tries to convince the reader that Zionist Israel is the major obstacle to reconciliation with the Palestinians, though he is against violence of all sort, including from the Palestinian people. He outright rejects the military efforts of the PLO and looks instead for a reconciled Israel in which Jews and Arabs can live together.

Amazon Book Link: http://amzn.to/wMi0KA

Review by Kim Gentes

[1]Chacour & Hazard “Blood Brothers”. (Grand Rapids, MI: Chosen Books 1984), Kindle Location 325

[2] Ibid., Location 613

[3] Ibid., Location 1158

arab,

arab,  blood brothers,

blood brothers,  chacour,

chacour,  christian,

christian,  conflict,

conflict,  elias,

elias,  israel,

israel,  jew,

jew,  melkite,

melkite,  palenstinian,

palenstinian,  priest,

priest,  reconciliation in

reconciliation in  Book Review,

Book Review,  Church,

Church,  Community,

Community,  Grief,

Grief,  Justice,

Justice,  Leadership,

Leadership,  Loss,

Loss,  Persecution,

Persecution,  Reconciliation

Reconciliation  Tuesday, August 23, 2011 at 4:06PM

Tuesday, August 23, 2011 at 4:06PM "Forgiving means abandoning your right to pay back the perpetrator in his own coin, but it is a loss that liberates the victim."1

This lithe statement makes clear what equation is required for solving the problem of reconciliation. It was this solution that was the heart and soul of the transformation that took place in South Africa in the last 20 years. As a prominent member of the ecclesiastical and moral movements within the South African nation, Desmond Tutu became an icon of leadership for the black people who had suffered for decades under the crushing blows of apartheid. Tutu's book "No Future Without Forgiveness" is a personal memoir of his process and involvement with the, now famous, Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which he chaired during its lifetime.

The commission's broad mission, mandated by the South African President Nelson Mandela, was two-fold. First, it was to engage a process which would discover the truth of the apartheid operation in South Africa, expose it, allow for confession of its terrible acts by the people responsible (under the auspices of a later process to amnesty), and look for verbal contrition related to those confessions. Secondly, it was to engage victims as well, and call for their testimony and courage to reveal the stories of their abuse and suffering. A later process of both amnesty and reparations was to follow the revelations brought out by the TRC's findings.

What is most surprising about the commission is not, however, the stories of horror brought forth by the victims, or even the admissions of guilt submitted by many of the perpetrators. What is most surprising is the consistent, real, verbal, physical, on-the-spot, heart-rending examples of forgiveness. In profound case after case, magnaminity flowed like the waters of healing through so much of the proceedings of the commission that the TRC, South Africa and Tutu himself became examples of the power of forgiveness for the entire world. Though the stated title of the commission included reconciliation, there was no true step in the process of its actions that guaranteed or even offered such a wild promise. Yet it encountered it time and again.

Tutu is quick to point out the failings, weaknesses, hurdles and sufferings of their efforts, as well as their successes and is all the bigger a human being for doing so. "No Future Without Forgiveness" is a definitive example of the gospel of Jesus becoming the good news for the 20th (and 21st) century human race. Without casting any religious encumbances on either the procedings or his book readers, Tutu guides both through a process of healing the begins with confession, leads to admission, responds with forgiveness and goes forth with reconnection and the beginnings of possible relationship.

While topic and content are ultimately the pinnacle of concerns for the human race, as a writer, Tutu runs slightly aground on a few points, but never endangers the work with irreprable harm. First, the book has several sections that repeat examples and recite cases. This would not seem odd, as the importance of the work demands repetition, but this happens so often and with such detail one believes a broader editorial presence might have scaled back some of the recitings as thinner references, with restating much detail. Second, there are several times when grammatical sense and structure were not attended to. Slight deference is given for the uniqueness of South African english which may fall askew from American english (or vise versa), but I found a few examples of clauses without whole sentences, which seemed odd. Both of these relatively minor authorship roadbumps seem like they could have been avoided by good editorial management.

That said, the book is engaging, unique and profoundly needed. So far beyond being a great book with no practical application, "No Future Without Forgiveness" is a success not because it is a literary juggernaut, but because it is an archive of amazing action that literally changed a nation. Saying more about the content is not necessary, as the story is a compelling and inviting read for anyone who wishes to take it up.

An unstoppable book with an unstoppable message.

Product Link on Amazon: No Future Without Forgiveness

Review by

Kim Gentes

[1]Desmond Tutu, "No Future Without Forgiveness", (New York, NY: Random House 1999), Pg 272

apartheid,

apartheid,  blacks,

blacks,  commission,

commission,  desmond tutu,

desmond tutu,  leadership,

leadership,  no future without forgiveness,

no future without forgiveness,  racism,

racism,  reconciliation,

reconciliation,  south africa,

south africa,  tutu,

tutu,  whites in

whites in  Book Review,

Book Review,  Grief,

Grief,  Leadership,

Leadership,  Loss

Loss