Book Reviews (by Kim Gentes)

In the past, I would post only book reviews pertinent to worship, music in the local church, or general Christian leadership and discipleship. Recently, I've been studying many more general topics as well, such as history, economics and scientific thought, some of which end up as reviews here as well.

Entries in conflict (4)

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team - Patrick Lencioni (2002)

Thursday, February 14, 2013 at 12:53PM

Thursday, February 14, 2013 at 12:53PM Years ago, I was serving on the executive team with one of the best managers I've ever worked with. His name was Chris. He had the most highly attuned sense of team-building and leadership that I had seen in a CEO. One of the first books Chris asked our team to read was "The Five Dysfunctions of a Team" by Patrick Lencioni. This last month, I revisited this book and read it again. It struck me again as a succinct and actionable treatise for any team.

What it exposes is the real reason that most teams fail- people are often more interested in personal accomplishment than achieving team success. Lencioni artfully narrates what he calls a "leadership fable" of a new CEO who comes into a high-tech company to try to turn it around. The scenario that unfolds sounds so familiar to any of us who have worked in a senior staff meetings that it's a little indicting just reading the book, let alone considering doing something based on it. But that is why using a narrative is so powerful.

Lencioni recognizes that we must hear these truths in a reasonably real context rather than simply have them extrapolated as another "5 steps to corporate success" or such business book claims. And this book does exactly that. The reader is allowed to enter the world of DecisionTech, a fictitious Silicon Valley startup with everything going for it- except results! The story strips back the layers of dysfunction in the leadership team to its very core, and draws some deft steps at deconstructing the failures and reconstructing a strong working team. Not only do you end up seeing the components, people and issues for the raw things they are, but you begin to see (by the dissociation of story-telling) how those might be addressed in your own situations.

The author doesn't leave it to story either. Once the narrative has completed, Lencioni retraces the core points of the "Five Dysfunctions" and you are given concrete steps to moving to building an effective team that can produce results. Since this book has become one of the best selling books on business leadership in the last 10 years, I am guessing many people have found this sage advice. I would be in that camp. Some of the observations and truths pointed out here are so poignant they may seem obvious. Yet, the real problem is that we often stay mindlessly aware of these "800lb gorilla issues" that are in the room, but fail to address them. Lencioni faces this head on and doesn't blink.

This is an excellent book, and it gets better each time I read it. I will be going back and reading it again in the next couple days. It's usable, thoughtful, and potentially revolutionary (to those who will act). The book is short (239-240 pages, depending on the version you read) so you should be able to read it in just a few hours. Well worth the time.

Amazon Book Link: http://amzn.to/VUpdNl

Review by Kim Gentes

From Beirut to Jerusalem - Thomas Friedman (1996)

Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 11:25PM

Sunday, February 26, 2012 at 11:25PM  “From Beirut to Jerusalem” is the thoughtful memoirs of a Jewish-American journalist based in the Middle East during the 70’s and 80’s. Thomas Friedman was The New York Times bureau chief for five years in Beirut and similarly served as the Israel bureau chief based in Jerusalem, after his term in Lebanon. Friedman writes with the inquisitive mind of a reporter, but the analytical prowess of a seasoned diplomat. What I loved most about this book is the insightful concepts that Friedman mines from his experiences in the Middle East, all the while embedding the reader in the personal narrative of his life in the conflict-ridden countries in which he worked and lived.

“From Beirut to Jerusalem” is the thoughtful memoirs of a Jewish-American journalist based in the Middle East during the 70’s and 80’s. Thomas Friedman was The New York Times bureau chief for five years in Beirut and similarly served as the Israel bureau chief based in Jerusalem, after his term in Lebanon. Friedman writes with the inquisitive mind of a reporter, but the analytical prowess of a seasoned diplomat. What I loved most about this book is the insightful concepts that Friedman mines from his experiences in the Middle East, all the while embedding the reader in the personal narrative of his life in the conflict-ridden countries in which he worked and lived.

For example, after the reader learns about Friedman’s first weeks in Beirut and even the bombing of his own apartment building, the author has the presence of mind to draw out a poignant moment in the lives of a common citizen:

“In the United States if you die in a car accident, at least your name gets mentioned on television,” Hana remarked. “Here they don’t even mention your name anymore. They just say, ‘Thirty people died.’ Well, what thirty people? They don’t even bother to give their names. At least say their names. I want to feel that I was something more than a body when I die.”[1]

But Friedman isn’t just reminiscing about the incidentals of common hardships (valuable as that is), he is learning the under-girding truths of the society in which these things are occurring, and synthesizing those ideas into concepts that matter at the macro level:

What made reporting so difficult from Beirut was the fact that there was no center—not politically, not physically; since there was no functioning unified government, there was no authoritative body which reporters could use to check out news stories and no authoritative version of reality to either accept or refute; it was a city without “officials.”[2]

It is this dual gifting that makes the entire book both readable and insightful. Friedman does a good job at nuancing the opinions of the book with broader opinions of the people involved in the meta-stories. You hear about the close, personal work and friend relationships he has with Lebanese, Syrian, Jewish, and Palestinian individuals whose own stories (both tragic and hopeful) color the pages of this book. He tries to give you fair vantage points of all the people he meets- even when they are people he is being threatened by! For example:

Most of the PLO officials and guerrillas with whom I dealt regularly knew I was Jewish and simply did not care; they related to me as the New York Times correspondent, period, and always lived up to their claims to be “anti-Zionist” and not “anti-Jewish.”[3]

Friedman is aware that the world in which he is working is fraught with misunderstanding or indifference- or sometimes both. It is that misunderstand that ultimately leads to conflict and death. The book repeats this cycle, even as Friedman makes his personal journey from the US to Beirut, to Jerusalem and back to the US. The book is clear that there is a price for not paying attention to others, and not addressing the real issues, as he says powerfully:

The similarity between Israel and Lebanon is rooted in the fact that since the late 1960s both nations have been forced to answer anew the most fundamental question: What kind of state do we want to have—with what boundaries, what system of power sharing, and what values?

...both the Lebanese people and the Israeli people have failed to resolve their differences on these fundamental questions, and have each become politically paralyzed as a result...

Whereas in Lebanon the Cabinet was ineffectual because it represented no one, in Israel the Cabinet was ineffectual because it represented everyone. In Lebanon they called the paralysis “anarchy” and in Israel they called it “national unity,” but the net effect was the same: political gridlock.[4]

The author doesn’t simply cover the details of Lebanon and Israel. He also explores the connections with important middle east entities, both as they impact his host countries and as their own stories restate the tragic narrative of violence in the region. He describes the tragic story of the city of Hama, Syria, whose uprising against its government and brutal ruler President Hafez Assad led to its obliteration, along with tens of thousands of its citizens. Friedman also explores the regime of Saddam Hussein, in Iraq, and its terrible use of force to repress uprisings against its authoritarian government. He even provides a brief historical and contextual lesson for the entire region by describing the Ottoman empire, its end and dissection after World War I, and how the creation of modern Middle East countries forced tribes, languages and religions to be grouped in countries that were artificial constructions of the British and French powers (which is arguably considered one of the reasons for much internal strife within those countries, even to this day). The book explores the PLO and its self-aggrandizing leader Yasir Arafat, with character and historical descriptions as well. So much is covered in this books 526 pages, it is impossible to summarize it here. Additional highlights include the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the US Marine’s peace keeping mission in Beirut, the Palestinian intifada (uprising), the details of Egypt/Israel’s war and eventual treaty, and much more.

Friedman does not allow his own heritage as a Jewish American to slight his integrity as a reporter. One of the clearest examples of this is his clarity of understanding with the desire of his Jewish compatriots to establish their homeland in the ancient land of Palestine- connected once again to the cities, locations and historical places that have profound meaning to the Jewish heritage. But he isn’t taken up in either Zionist or anti-Jewish extremes. He sees how easily the oppressed nature of the Jewish psyche can turn from being the historical oppressed to the vengeful oppressors:

As I watched these young Jewish terrorists in their yarmulkes and long beards walking around the courtroom, I could not help but be struck by their self-confidence and self-righteousness. The way they strutted about, chatting with their wives, chomping on green apples, and almost literally turning up their noses at the judge, was galling. I had seen the same arrogance among members of Hizbullah, the Party of God, in Beirut. These were simply the Jewish version.[5]

As the book rounds the corners of Friedman’s experience, the author doesn’t fail to speak of the powerful impact of the American superpower on all the nations of the middle east. Friedman fairly criticises and compliments the pertinent aspects of US policy, leadership and communications. Like he does with all the parties involved, the author mines the nuggets that we rarely think about but, in fact, reflect the pertinent meta-narratives that could make a significant difference.

Israeli political theorist Yaron Ezrahi always liked to tell me that the most important thing an American friend can offer Arabs and Israelis is American optimism—exactly the kind of innocent can-do optimism that the Marines brought to Beirut. The Marines’ almost childlike belief that every problem has a solution, that people will respond to reason, and that the future can triumph over the past is a wonderful thing, Yaron would remind me. It is a trait which Americans should never be ashamed of.[6]

Friedman gets to specifics, speaking about Israeli Prime Ministers, PLO leader Arafat (and others), and even US diplomats. My favorite section of the book is actually after the final chapter. In the epilogue, Friedman drills down to succinct, explicit steps that could be helpful for addressing the conflict of the Palestinian and Jewish /Arab conflict. His insights here are most thoughtful, although now perhaps more hopeful than the post-9/11 world might concede (his book is written in 1996, before the WTC and 9/11 attacks). Still, I believe it is the optimism that Friedman points to (in his quote about Americans) that can lead his other points to fruition. This is an expansive, engaging, personal, yet grandly comprehensive book. Very well done and worth reading.

Amazon Book Link: http://amzn.to/zp20ra

Review by Kim Gentes

[1] Friedman, Thomas L, “From Beirut to Jerusalem”. (New York, NY: Anchor Books/Doubleday 1996)., Kindle Edition, Page 29

We Belong to the Land - Elias Chacour / Mary E. Jensen (2001)

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:29PM

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:29PM  Elias Chacour is a Melkite Palestinian priest living in Galilee. He is a central figure in reconciliations efforts to draw an end to the persecution and expulsion of Arabs from the Jewish country of Israel. The territory occupied by Israel following the establishment of the state (after World War II), created a polarized ethnic feud, perpetrated by Zionist Jews (claims Chacour) that have resulted in the persecution of Palestinians. In his book “We Belong to the Land”, Chacour outlines his struggles as a priest and local leader in a the community of Ibillin. In that small community, Chacour fights to build unity amongst different people groups, religions and ages. His efforts include building a unified inter-faith group, constructing and managing a secondary school and high school, and eventually a college. The struggles Chacour outlines, explore the racist and discriminatory efforts of Jewish establishment officials to minimize the rights and opportunities of Palestenians in an effort to force them to leave the country (allowing the Jews to have a completely Zionized state).

Elias Chacour is a Melkite Palestinian priest living in Galilee. He is a central figure in reconciliations efforts to draw an end to the persecution and expulsion of Arabs from the Jewish country of Israel. The territory occupied by Israel following the establishment of the state (after World War II), created a polarized ethnic feud, perpetrated by Zionist Jews (claims Chacour) that have resulted in the persecution of Palestinians. In his book “We Belong to the Land”, Chacour outlines his struggles as a priest and local leader in a the community of Ibillin. In that small community, Chacour fights to build unity amongst different people groups, religions and ages. His efforts include building a unified inter-faith group, constructing and managing a secondary school and high school, and eventually a college. The struggles Chacour outlines, explore the racist and discriminatory efforts of Jewish establishment officials to minimize the rights and opportunities of Palestenians in an effort to force them to leave the country (allowing the Jews to have a completely Zionized state).

Unlike his other book, Blood Brothers, Chacour focuses this book on details of injustice, his programs and building efforts, his organization and leadership across Galilee, Israel and around the world. Much of the book includes his philosophical and rhetorical foundation for his opposition to Jewish radicalism within the occupied territories where Palestinians once thrived. Chacour is a brilliantly practical man, with wit wisdom and far reaching appeal. He intuits things that others only come to understand through years of deep thinking and research. For example, he speaks eloquently about the value of human beings:

"The true icon is your neighbor", I explained to my companions on Mount Tabor, "the human being who has been created with the image and with the likeness of God..."[1]

We Belong to the Land especially follows the details of corruption not only with the the Zionist corners of the Israeli government, but scandalous and complicit efforts of Chacour’s own overseer, the local Bishop of his church’s diocese in which he is serving. In fact, corruption of values across the church and even “western” society is brought largely into focus by Chacour’s damning indictments of the “Christian” supported US government’s efforts to support and sustain Israel’s policies.

Much of what Chacour elucidates he does so as we follow the story of his building of his local school in the community of Ibillin. The seemingly simple matter of securing a building permit becomes the plot device which allows us to explore the broader injustices to both Ibillin and the Palestinian people. But Chacour is careful not to become the very thing he despises, which is common a trend. Instead of hating the Jewish people who have repressed the Palestinians in the country, he constantly calls for a fellowship of love in which both people’s can live in harmony within the land. His most articulate arguments become prayers of commonality that we can all join in. He says,

Human worth, human qualities, are much more important than Jewish, Palestinian, or American nationalism, peoplehood, or land. Sometimes it seems to me that Zionism pushes the Jews to Zionize themselves rather than humanize themselves.[2]

His thesis in the book centers around his belief that the thousands of years of living in the land have united the Palestinians with the essence of what it is to be an agrarian people.

Mobile Western people have difficulty comprehending the significance of the land for Palestinians. We belong to the land. We identify with the land, which has been treasured, cultivated, and nurtured by countless generations of ancestors.[3]

The examples and clarity of Chacour’s convictions become crystal clear. He is intent on peaceful freedom for Palestinians within the national borders of Israel. But for all his brilliant practicality, Chacour takes his altruism and misapplies it at least once, when he says,

God does not kill, my friends. God does not kill the Ba’al priests on Mount Carmel, or the inhabitants of the ancient city of Jericho. God does not kill in Nazi concentration camps, or in Palestinian refuge camps, or on any field of battle.[4]

It is obvious to many that Elias Chacour reflects the best of a heart of justice found in our world today. Yet, we cannot, even in our desire for justice, pretend to know more than God. God, in fact, is more just than us, and more loving than us. But He did kill, not just people in the Old Testament (uncountable peoples of all the inhabited the land of Canaan that were wiped out as Israel settled and conquered the region, including both of the instances of Ba’al preists and Jericho inhabitants that Chacour blatantly denies God is responsible for, though the text clearly indicates He is), but people in the New (Ananias and Sapphira, plus the multitudes of opposition to Jesus righteous judgments in John’s Revelation). While we have a hard time reconciling those actions to our comprehension of a loving God, we cannot dismiss God’s actions of these final earthly judgements of death as though they didn’t happen or he didn’t mean it. He did, and He is still God. Misstating these facts to shape God into your vision of justice does not do God, himself, any justice.

The other (more dangerous) issue to me on the above quote is that Chacour combines things that God clearly does instigate (Jericho and Mt. Carmel) with things that man (or perhaps Satan himself) have deeply inspired and carried out (Nazi Germany, Palestinian refuge camps). One cannot attribute all evil actions to God, unless one decides to make man faultless of his own predilections, choices and sinfilled actions. Of course, there is the grand question "why do bad things happen to good people" and why is there suffering and hurt. The short answer is - sin. But there are rife volumes and lives spent on the topic, so I won't pretend to sort that all out here. But munging God's clear actions and man's sinful ones in a single list of activity (as though they belong together) is a terribly grievous error, for which I cannot let go without mention.

My confidence in his writing flags when I see that he never actually deals head on with the specific claims of moderate Zionist Jews who believe they are following an edict from God to reclaim the land granted to Abraham (and therefor, Israel) by Yahweh. I am convinced that he is a man of integrity, and certainly not afraid of confrontation and working against the norm, so it surprises me that he never broaches the subject from the Jewish point of view, even if to discredit the weak points of their argument. Second, he takes the broad tact that all Christians (and especially all American Christians) are somehow in rabid support of Jewish Zionism. Again, he washes his hands of details and accuses the US of global blood guilt without taking on specifics and details from which a more reasonable (balanced) response could be given to his condemnations. It feels a little like he deals so beautifully with the story of the Palestinians that he doesn’t want to address the 800lb gorilla issue in the room- the contrary story which lives along side him every day- the Jewish Israeli claim to the land of Canaan, promised to them through the Old Testament scriptures.

I feel quite guilty having brought up what I think are short comings of his fine book, since one feels ultimately humbled and speechless in light of such a great witness of Christ’s love and reconciliation. I am very glad to be wrong on all my points, and would feel better about it. For me, the things I have said negatively don’t deter from his great accomplishments or his stature as a preeminent leader of peace in our generation. It is hard not to love the heart, desires and unbelievable work ethic of Elias Chacour. The accomplishments he has made in the midst of being a nearly singular voice within a tragic situation is remarkable. He has much to teach the world about the true nature of reconciliation and its practical outworking. I would love to meet him.

Amazon Book Link: http://amzn.to/w5PTZ2

Review by Kim Gentes

[1]Chacour, Elias & Jensen, Mary “We Belong to the Land”. (Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press 2001), Pg. 46

[2]Ibid., Pg. 69

[3]Ibid., Pg. 80

[4]Ibid., Pg. 163

arab,

arab,  chacour,

chacour,  christian,

christian,  conflict,

conflict,  elias,

elias,  israel,

israel,  palestine,

palestine,  palestinian,

palestinian,  priest,

priest,  reconciliation in

reconciliation in  Book Review,

Book Review,  Church,

Church,  Community,

Community,  Grief,

Grief,  Justice,

Justice,  Leadership,

Leadership,  Loss,

Loss,  Persecution,

Persecution,  Reconciliation

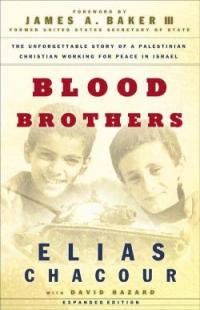

Reconciliation Blood Brothers - Elias Chacour / David Hazard (1984)

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:15PM

Tuesday, January 24, 2012 at 3:15PM  "Blood Brothers" is the first book from Palestinian Israeli Elias Chacour. Elias is a Christian priest and community leader in Galilee, Israel. He lives and serves his community of Palestinian Christians in a village of Muslim, Druze and Christian villagers. This book is the personal story of his youth, the expulsion of him and his family from his home village of Biram, his training as a Melkite priest, and his eventual work in the ministry of bringing hope to a broken and terrified group of alienated Arabs in Jewish Israel. Unlike his other book We Belong to the Land, Chacour focuses more poignantly in Blood Brothers on his personal and family life. Most profoundly, he explores the character of his father who serves as an arch-type for both God and the image of what good men can be. Elias Chacour treasures and follows this image into a lifetime of seeking reconciliation, hope and love for the Palestinian people of the village of Ibillin.

"Blood Brothers" is the first book from Palestinian Israeli Elias Chacour. Elias is a Christian priest and community leader in Galilee, Israel. He lives and serves his community of Palestinian Christians in a village of Muslim, Druze and Christian villagers. This book is the personal story of his youth, the expulsion of him and his family from his home village of Biram, his training as a Melkite priest, and his eventual work in the ministry of bringing hope to a broken and terrified group of alienated Arabs in Jewish Israel. Unlike his other book We Belong to the Land, Chacour focuses more poignantly in Blood Brothers on his personal and family life. Most profoundly, he explores the character of his father who serves as an arch-type for both God and the image of what good men can be. Elias Chacour treasures and follows this image into a lifetime of seeking reconciliation, hope and love for the Palestinian people of the village of Ibillin.

One such powerful example is his father’s statement about Jews and Palestinians, which he declared before the full extent of persecution would begin for the Palestinians:

“But How do we know the soldiers won’t harm us?” Rudah pressed him.

Father smiled, and all the tension seemed to relax. “Because,” he said, “the Jews and Palestinians are brothers-blood brothers. We share the same father, Abraham, and the same God. We must never forget that. Now we get rid of the gun.”[1]

This image turns out to be misinformed, though hopeful premonition to the tragedy that would ensure. After taking over the land of Palestine, the Jews of Israel began to programmatically terrorise the people of the rural villages such as Biram. Demolishing their homes and farms and confiscating the land became the program of the Zionist Jews. Even thought Chacour’s father has his land taken from him and his home destroyed, his connection to the land and its plants shows a level of care foreign to us.

I could scarcely believe it! His life's work had just been torn from his hands. His land and trees-the only earthly possessions he had to pass on to his children-were sold to a stranger. And still Father would not curse or allow himself to be angry. I puzzled at his words to us. Inner peace. Maybe Father could find this strength in such circumstances. I doubted that I could....

Father's other response to the sale of his land was more of a wonder to me. In a few weeks we heard that the new owner of our property wanted to hire several men to come each day and dress the fig trees, tending them right through till harvest. Immediately, Father went to apply for the job, taking my three oldest brothers with him. They were hired and granted special work passes, the only way they could enter our own property.[2]

Elias portrays his father with such magnanimous character that he seems barely real to our western sensibilities and callousness. The story of Blood Brothers is much deeper than just Elias Chacour’s life, it is a story of the non-violent Palestinians who are persecuted as evil by Israeli government programs meant to lodge them from hope and from land within the Galilee communities. Chacour is not just a concerned priest, he is a thoughtful change agent and leader. Speaking about the inversion of the Jews from persecuted to the persecutors he says :

Now I determined to find out how a peaceful movement that had begun with a seemingly good purpose-to end the persecution of the Jewish people-had become such a destructive, oppressive force. Along with that determination, I was driven by a respect for history that Father had planted in me. Did the seeds of our future hope lie buried in our past, as he had so often said?[3]

Elias is brilliant to turn to the teaching of his father to recall the thought that history can teach us and, perhaps if heard, can lead us back together. Blood Brothers tries to convince the reader that Zionist Israel is the major obstacle to reconciliation with the Palestinians, though he is against violence of all sort, including from the Palestinian people. He outright rejects the military efforts of the PLO and looks instead for a reconciled Israel in which Jews and Arabs can live together.

Amazon Book Link: http://amzn.to/wMi0KA

Review by Kim Gentes

[1]Chacour & Hazard “Blood Brothers”. (Grand Rapids, MI: Chosen Books 1984), Kindle Location 325

[2] Ibid., Location 613

[3] Ibid., Location 1158

arab,

arab,  blood brothers,

blood brothers,  chacour,

chacour,  christian,

christian,  conflict,

conflict,  elias,

elias,  israel,

israel,  jew,

jew,  melkite,

melkite,  palenstinian,

palenstinian,  priest,

priest,  reconciliation in

reconciliation in  Book Review,

Book Review,  Church,

Church,  Community,

Community,  Grief,

Grief,  Justice,

Justice,  Leadership,

Leadership,  Loss,

Loss,  Persecution,

Persecution,  Reconciliation

Reconciliation